INTERVIEW | Deborah Kruger

10 Questions with Deborah Kruger

Surface design and patterning have influenced Deborah Kruger’s work since her textile design training at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York. She has taught, lectured, and exhibited throughout the US, Mexico, Europe, and Australia since the 1980s.

Recent career highlights: Finalist for the 2023 Arte Laguna Prize in sculpture and installation with an exhibition at the Arsenale Nord in Venice, Italy. Featured artist at the World of Thread Festival in Toronto, Canada. Kruger’s work was also featured in 2023 Follow the Thread in New York City. In 2022, her solo exhibition “Plumas” was on view at PRPG.mx gallery in Mexico City. Kruger has been in two recent international Biennales, including the 2021 Art Textile Bienniale in Australia and the 2022 Rufino Tamayo Bienal in Mexico City.

The Museum of Arts and Design in New York City has just acquired two of her large-format environmental works, and they will be exhibited in 2024.

Kruger’s work has appeared in numerous international art press and blogs, including ArteMorbida, a textile magazine based in Rome, Italy; ArtDaily.com in Mexico City; Considering Art in London, UK; Art Speil in New York City; Handwerken Magazine, a textile magazine, the Netherlands; and Fibre Arts Australia.

Kruger has attended residencies at the Millay Colony for the Arts, Austerlitz, NY, and La Porte Peinte Centre, Noyers-sur-Serein, France. In September 2024, Kruger will attend a residency at the Icelandic Textile Center.

Kruger has a production studio in the lakeside village of Chapala, Mexico, where her team-based art practice provides jobs and empowerment to local Mexican women.

Deborah Kruger - Artist Portrait at Avianto solo exhibition in front of Fragmentation

ARTIST STATEMENT

Deborah Kruger’s latest artwork focuses on the tragic losses of the 21st century, specifically the impacts of human-induced climate change and habitat fragmentation on bird extinction.

Drawing and researching endangered birds is the backbone of her art practice. The feathers in her textile paintings and sculptures are fabricated from recycled plastic hand silk-screened with images distilled from her drawings. These feathers are overprinted with text about the plight of endangered birds and also text in endangered indigenous languages such as Yiddish, Ladino, Tzotzil, and Cho’lol, whose last living speakers are in steep decline.

The feathers used in all her artwork appear to be made from paper or textiles, but on closer inspection, you can see that they are actually plastic. By using recycled plastic, the artist embeds an additional narrative that addresses the relentless consumption driving the loss of birds and human habitats. Kruger has been able to use her prior training in wallpaper and textile design to address global ecological and cultural concerns.

At a time when climate change is informing so many conversations, Kruger hopes that her environmental artwork invites dialogue about the importance of preserving wild spaces, animals, especially vulnerable birds, and protecting habitat for all species, including humans.

Making art from recycled materials reminds viewers that we can all do something to reduce our ecological footprint. Incorporating endangered birds and languages in her environmental artwork prompts us to remember how our lives are enriched by indigenous culture and how art continues to have the power to inspire new thoughts and action.

INTERVIEW

Please introduce yourself to our readers. How is Deborah Kruger in three words

Environmental Fiber Artist

Before turning to visual arts, you studied textile design at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York. How does this background help you with your current work? And how did this training influence your current practice?

I received excellent design training at the Fashion Institute of Technology. I studied textile design, silk screening, weaving, and textile research, all of which I use in my art practice. Being immersed in a fashion and decorative design culture gave me permission to include these themes in my artwork. Although I tackle environmental themes, I do so in a decorative context, which I think makes my art more accessible. I also studied ethnic textiles and costume design, and this background is apparent in my series of works that echo Huipils from Latin America and Kimono from Korea and Japan.

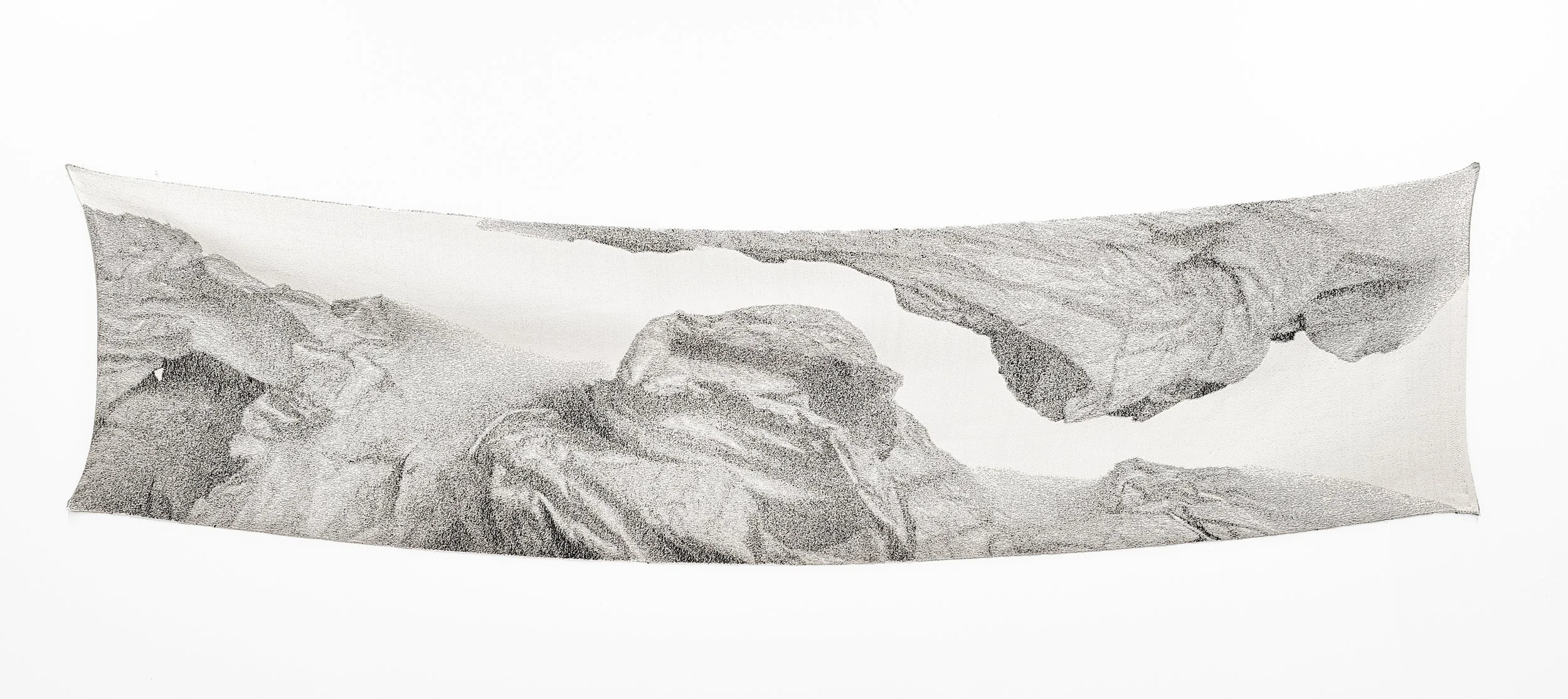

FRAGMENTATION, hand screen-printing on recycled plastic, hand and machine sewing, pellon, acrylic paint, 76.5x169x4 in, 2021 © Deborah Kruger

Fragmentation is a curving three section piece based on the map of San Luis Potosi, Mexico, a state where rainforest clearcuts are threatening many bird species, indigenous languages and cultures. The feathers are made from recycled plastic, hand screen-printed with images of endangered birds and overprinted with text in endangered languages.

Speaking of practice, you work with a mixture of sculpture, installation, painting, and drawings, which you incorporate into your final works. How did you come up with this concept?

There’s something exciting about working across multiple media. When I started using traditional women’s clothing as an inspiration, it naturally morphed into a sculpture because referencing the body infers three-dimensionality. Installation takes the work off the wall and into the exhibition space, where viewers have a more immediate physical encounter. Using various media feels right and organic.

A focal element in your art is using elements that recall different materials, such as recycled plastic that mimics textiles or paper. Why did you choose to follow this route?

Although I have used textiles in my artwork for years, I came to a crossroads about seven years ago and felt that my materials were not effectively conveying my content. I paused for a year to explore other options, and while this was nerve-wracking, I eventually found that working with recycled plastic embedded a silent narrative that was cohesive with my themes. Plastic, after all, is one of the culprits of global pollution, and it also refers to the rampant consumption that drives habitat destruction. I love that my pieces still evoke fiber and paper.

REDWING, hand screen-printing on recycled plastic, hand and machine sewing, wrapping, waxed linen thread, 60x110x2 in, 2023 © Deborah Kruger

Redwing is a mural-size piece that is named for the many beautiful red birds around the world that are now endangered as a result of habitat fragmentation. Redwing is constructed in 3 sections in order to facilitate shipping. All the feathers are created by hand screen printing on recycled plastic, using images of endangered birds and text in endangered indigenous languages.

ACCIDENTALS, hand screen-printing on recycled plastic, hand and machine sewing, wrapping, waxed linen thread, sisal, 92x167x6 in, 2023 © Deborah Kruger

Accidentals is a mural sized piece whose title is a based on the word that describes birds that appear in habitats where they aren't generally found, often as a result of habitat fragmentation. I make the feathers from recycled plastic, screen printed with images of endangered birds and overprinted with text in endangered languages such as Yiddish, Shorthand, numerous indigenous languages and excerpts of Rachel Carson's Silent Spring. Accidentals has recently been acquired by the Museum of Arts and Design in New York City.

Another focus in your work is the environment and the impact of human activities on it, especially confronting the current climate crisis. What do you think is the role of art and artists in addressing such themes?

Artists have always given voice to the issues of every time period throughout history. We process the world visually, as writers have processed history with words. Whether we drew on cave walls, painted religious icons, or recorded the landscapes and people of our time, we are pulled to document and narrate what is going on around us through images, color and texture. Being an environmental artist addressing the threats to our climate feels like being part of a long lineage of social narrators.

In your work, you parallel endangered species, environments, and populations as you use words and phrases from indigenous languages that are almost extinct nowadays. What is the correlation, in your opinion, between these populations and the territories they inhabit?

Native traditions are governed by concern for the well-being of future generations. Not so in the current atmosphere of corporate greed and relentless consumption. My research-based practice revealed that habitat fragmentation, which endangered birds, concurrently was threatening indigenous people, languages, and cultures around the world. The American environmentalist Rachel Carson suggested that ‘The more clearly we can focus our attention on the wonders and realities of the universe, the less taste we shall have for destruction.”

ROPA ARCO IRIS, hand screen-printing on recycled plastic, hand and machine sewing, wrapping, waxed linen thread, 53X45X2 in, 2023 © Deborah Kruger

Ropa Arco Iris is part of a series of artwork inspired by the Huipil, a traditional women's garment from Chiapas, Mexico and Guatemala. The indigenous women from these regions are famous for their hand weaving perfected over thousands of years. There are vertical stripes in the piece that echo the woven construction of huipils. The colors of Ropa Arco Iris reflect the colors of the rainbow, thus its name. This wall relief is hand screen-printed on recycled plastic, hand and machine sewing, wrapping, and waxed linen thread. I have used women's clothing as a source of inspiration for many years. Indigenous people are at risk due to habitat fragmentation along with birds and other species.

KIMONO 2, hand screen-printing on recycled plastic, hand and machine sewing, wrapping, waxed linen and wire thread, oilstick, bamboo, 59 X 39 X 2 in, 2023 © Deborah Kruger

Kimono 2 evokes shape and sensibility of a kimono. The colors are primarily white with a dramatic blue central column of color. The piece is made in 3 sections that are sewn onto a wrapped bamboo stick with waxed linen thread. The feathers are made from recycled plastic, hand screen-printed with images of endangered birds and overprinted with text in endangered languages such as Yiddish, Shorthand, numerous indigenous languages and excerpts of Rachel Carson's Silent Spring.

What is the role of your drawings in your creative process? Judging from your statement, they are the first step in your work; how do you use them and incorporate them into the final piece?

Drawing endangered birds is the backbone of my art practice. Drawing, like meditation, is a deeply centering and profound way to see the world. When I am drawing the endangered birds that I research, I deepen my knowledge of them and fall in love with them. The drawings appear in my work in many guises. For the silk screens that I print on recycled plastic, I reduce the size of the drawings into silhouettes and use these images to design each silk screen, which typically includes four to five different birds. My textile design background really comes in handy for this aspect of my art practice! My floor installations are created with shattered ceramic plates that have my full-size bird drawings hand-painted on each plate. When viewers look down on Broken, my floor installation, they see fragments of the drawings on the ceramic shards. Broken is a warning designed to bring our attention to the loss of our precious birds.

Is there any other theme you would like to tackle with your work?

I am feeling increasingly drawn to creating feathered sculptures, like Re-Dress, which reference not only women’s fashion but also the ongoing repression of women around the world.

BREASTPLATE, hand screen-printing on recycled plastic, hand and machine sewing, wrapping, waxed linen thread, 25 x 40 x 2 in, 2023 © Deborah Kruger

The feathers in Breastplate are cut into curved forms that echo the shape of bird feathers. This piece is built in layers and resembles a large version of a breastplate that is worn for protection or decoration. Wrapped sticks have appeared in my work for many years and in this piece they define the top edge of the piece. The feathers are made from recycled plastic, hand screen printed with images of endangered birds and overprinted with text in endangered languages such as Yiddish, Shorthand, numerous indigenous languages and excerpts of Rachel Carson's Silent Spring.

You have been exhibiting since the 1980s, as you recall in your biography. In your opinion, how did the art world change over the last few decades? And what is one piece of advice you would like to give to an emerging artist to thrive in today’s market?

One of the biggest changes in the art world has been the increasing visibility of women, especially marginalized women. For art to be truly universal, it needs to include all of our voices. Here’s my advice to younger artists: The more you stay true to yourself, your history, and your passions, the more authentic your art will become. Also, the most successful art is a seamless marriage of content and form; these need to be balanced across all of your artwork.

Lastly, what are you working on now? And what are your plans for 2024?

2024 is already shaping up to be an exciting year. I have shows lined up in Italy, Australia, Raleigh, NC (my base in the USA), and Bogota, Colombia. I will also spend September 2024 in a residency at the Icelandic Textile Center. I am deeply grateful for all of this visibility, and I thank the team at Al-Tiba9 for recognizing my work and bringing it to an international audience.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a promotional platform for artists to articulate their vision and engage them with our diverse readership through a published art dialogue. The artists are interviewed by Mohamed Benhadj, the founder & curator of Al-Tiba9, to highlight their artistic careers and introduce them to the international contemporary art scene across our vast network of museums, galleries, art professionals, art dealers, collectors, and art lovers across the globe.