INTERVIEW | Helena Eribenne

10 Questions with Helena Eribenne

Helena (née Chilo) Eribenne, a London-born multimedia artist of Nigerian descent, works across film, photography, performance art, theatre, installation, and music. She has collaborated with influential figures like Fluxus co-founder Benjamin Patterson, kraut-rock musician Holger Hiller, and jazz drummer John Stevens, among others. Based in Vienna since graduating from the Academy of Fine Arts in 2004, she focuses on time-based media, performance art, and conceptual time travel, for which she received the H13 Performance Prize in 2019.

Her work critiques post-colonialism, using 19th-century tools like the magic lantern and panorama to challenge colonial narratives embedded in the collective unconscious. These tools, once used to promote colonial ideologies, are reimagined in her art to highlight positive depictions of pre-colonial West African spirituality. Her workshops empower participants to replace manipulative colonial imagery with self-determined alternatives, destigmatizing African spirituality.

Helena’s art also explores neo-colonialism, incorporating photography, video, and live performance. Recent travels to China have influenced her research into spirituality and Traditional Chinese Medicine, while a planned 2025 trip to West Africa will deepen her studies into cosmologies, ecology, and indigenous healing practices. She aims to integrate these elements into her work, fostering greater understanding and decolonization of spiritual traditions. Helena lives and works in Vienna.

Helena Eribenne - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

Helena Eribenne is a multidisciplinary storyteller whose work spans film, photography, video, performance, and music. Her art explores socio-political themes, particularly focusing on time travel, timelessness, and Afrofuturistic ideas of finding a safe home beyond time and space. In her interactive performance and photo series Killing Time, she critiques time as a social construct, blending past, present, and future into a transcendent simultaneity. The series incorporates the character Tyche, an angel representing timelessness.

Her series Borders addresses the geopolitical impacts of forced migration, inspired by her experience photographing refugees at a center in Austria during the 2015 migration crisis. Shoes and feet, symbolizing life’s journeys, feature prominently in her feminist critiques, linking high heels to patriarchal oppression and Freud’s theories, as well as fairy tales like The Red Shoes.

In Smells Like Teen Spirit, she examines the paradox of fame, using 1970s male teen idols as subjects to critique the commodification of artists and the toll of fame on their lives. Her long-term project, Self-Destructive Stars and West African Cosmology, integrates Afrofuturistic narratives with pre-colonial West African spirituality and AI technology, aiming to replace colonial imagery in collective memory with self-determined ones.

Killing time, performance, 2020 © Helena Eribenne | Photo: Andrea Hladky

INTERVIEW

Your work spans film, photography, performance, theatre, installation, and music. How do these various mediums interact within your creative process, and how do you decide which medium best serves a particular concept?

These various mediums interact with my creative process. I don't choose the medium first, the idea comes together at the same time. For example, with 'Killing Time,' there was a photo series and a performance. I'm the photographer of my portraits, but I work with an assistant. The performance is filmed and uploaded onto my Vimeo channel, but it's good for people to see it alongside the portraits in an exhibition setting. With 'Love Thy Neighbour,' a documentary film, it started as an artist-in-residency at the border to the Czech Republic. I wanted to invite trafficked women from sex clubs in the Czech Republic to Austria to participate in workshops. The raising of awareness of sex trafficking can produce secondary exploitation, so in order to avoid that, I wanted the women to be able to express themselves through art workshops, resulting in an exhibition. Needless to say, they didn't attend. It was a nice but naïve idea. I didn't think of how trafficked women should cross the border as their passports are usually confiscated, so I ended up doing a photo series of the village we were focussing on, which led to the documentary "Love Thy Neighbour' being filmed.

Helena Eribenne © eSeL.at - Lorenz Seidler

You describe time travel, timelessness, and exploring other dimensions as key themes in your work. What first drew you to these concepts, and how do they relate to Afrofuturism?

Okay, I was first drawn to time travel when, as a child, I used to look at books with photographs from the Victorian era, and I used to look at these people in these black and white photographs, and I used to analyse them, and look at their clothing and their expressions, and I used to just think, what would it be like to be there? I would have loved to have been able to travel back in time and just experience that moment, but it was so hard for me to imagine it. I really tried. I'd look around me, and I'd see everyone in 3D, in real life, in living colour, and then I would look at these photographs, and I would think, how can I put myself in that period of time? The medium created a special kind of detachment that I found hard to get past. I tried but couldn't find myself there.

Then, I used to try to travel back in time to the films I would watch on TV and try to position myself in them. To be there. It was so interesting to analyse the different colour gradings, the types of cars, and the fashion, and to be able to notice the difference between television series and colour and black and white films made between 1966 and 1970, and distinguish between them. I watched films beyond the screen. Again, I would try to insert myself in those films and travel back into that time, a time before I was born and a time around when I was born. And it was just really hard, but in a way I got good at recognising which year a film was made, like a James Bond film or a TV series like The Saint.

When I came to Vienna in 1999, I finally felt that I had time-travelled. Everything here was so old-fashioned. It was like the banks closed for lunch. You couldn't get a debit card. They only arrived ten years ago or so. If you called up the gas board or the electricity board, somebody would answer the phone! It was brilliant. You didn't have to dial one for this or two for that. So, in that way, it was really old school. I loved it! But on the other hand, as far as Afrofuturism is concerned, I did actually start feeling like I've gone back in time negatively as well. I felt like a very racialised object in the eyes of the Viennese. I wasn't just Chilo Eribenne, as I was called then. I was someone who had to be re-routed back to Africa, no matter how much I explained that I was from London. And even though I was more accepted as a London-born subject, I was more like a good foreigner or a good black person being from London, rather than directly from Africa. I was more acceptable for Austrians. It was easier for me than my counterparts who had come directly from say Nigeria to 'integrate'. I still had to be confronted with being racialised though.

Okay, so, I used to tease my Austrian friends about how everything was so old-fashioned here, and one said to me that Gustav Mahler once said that, "when the world comes to an end, he'd move back to Vienna, because everything happens there 20 years later". And I thought that was really funny because it is still so true. So I started writing a play of my own experiences, being in Vienna, with, you know, a similar title, "When the world comes to an end, move to Vienna, because everything happens there 20 years later". And in that play, it was about getting into a time machine from London in 1999, wanting to go back to London 1974, but ending up in Vienna instead, and it's still 1999 but it looked like 1974. So it was kind of autobiographical, and it was really about this whole Afrofuturism thing of trying to find a place called home on earth or somewhere in the universe. In the play, my character ends up in an Afro-textured hairdressing salon, and meets her American counterpart there, who's also a black African, but, you know, the good black, the good African-American, rather than the one directly from the fictional African country that I named Akipultonko in the play. So that was my first foray into Afrofuturism, and it has developed since then.

Your work also deeply explores post-colonialism. Can you share how this influences your work and how you actively work on this concept?

So I suppose the longer I stayed in Vienna, the more I sort of delved into post-colonialism. And I was studying for my PhD and doing various film courses and stuff. And I don't know, I feel like somehow I was very late in developing my interest in post-colonialism because I was so into the idea of the brotherhood and sisterhood of the human community, that there's no race, there's just a human race and we are all one under the sun. But the more I looked into colonialism and post-colonialism and looking at this, the more frightening it became and the more I realised I had to deconstruct a lot of my own concepts, how I was blindly still colonised and how religion and the power of religion and what the British did in what is now the political state of or the republic state of Nigeria was so terrible and mind-bogglingly bad. It just really knocked me back. Today, I realise that there's still so much decolonising that needs to be done in my mind. That features a lot in my work, which is exactly the opposite of my initial intention. I wanted to be able to do what white male artists. They don't need to do that, do they? They don't need to work with gender or race so much. They should, though, and one day they may.

Killing time#1, c-print, 2020 © Helena Eribenne

Killing time#1, c-print, 2020 © Helena Eribenne

What role does your art play in conversations around post-colonialism and identity? Is art a valuable tool for raising awareness of such themes?

So latterly, I suppose, I started to explore time travel and Afrofuturism and postcolonialism all in one blend and started to do performances such as "Woman to Woman II" and "When Time Has Flown". There, I could work on time travel, Afrofuturism, postcolonialism, and decolonialism, and my favourite aspect is audience interactivity. So, the live audience can really become part of the stage performances, which is a lot of fun. So that's something that I'm working on today as well, to build an interactive time machine where you can really go back to pre-colonial Africa and experience what it was like before the Europeans arrived and experience the cosmology in a spiritual way because I was very interested in how the construction of Black women is quite often a Christian construction, obviously also a Muslim one and how to de-construct this image using "the master's tools".

Your work, shoes, and feet are recurring motifs in your production, particularly in projects like "The Constructed Photographic Image of the Self-Destructive Female Icon." How do these symbols connect to your feminist theories and critique of patriarchal systems?

As I was researching the chapter about feet and shoes in my dissertation, I was looking at the feet of Amy Winehouse when she was wearing these bloodied ballet shoes, and I was looking at the legs of Whitney Houston as she had blood running down her legs, and I found this to be a very interesting feminist portrayal of women being constructed by the camera as out of control and in need of being controlled by men. For me, shoes and feet are deeply feminist. I began to explore the connections throughout the history of how patriarchy has tried to control women. I haven't gone into the witch hunts, but I have gone into looking at fairy tales such as "The Red Shoes" by Hans Christian Andersen. The pubescent girl who's orphaned and sees these beautiful red shoes is punished for indulging in her beauty and love of dancing and partying. So you have these cautionary tales and these stories and these images that are constructed by the camera of these 20th-century icons; they are interesting in that they show that women who try to be independent, who try to go their own way, are then cut down at the foot. And so there's also a connection to the Ming Dynasty in China, where you had foot binding. I believe that women who wear high heels with pointed toes, in a way, are binding their feet. This is a kind of, in my opinion, self-subjugation to patriarchy. It's a form of foot binding, and it's also a form of self-punishment. Of course, there's also the Freudian aspect where you had the castration complex. So in a way, patriarchy punishes women who are liberated by binding their feet and by castrating them because their own fear of castration, as Freud says, is that the mother doesn't have a penis because she is castrated. It is missing! And so her son remembers the foot as the last thing he sees when he notices, while looking up his mother's skirt, that she is castrated. According to Freud, the foot is phallic and becomes a fetish. He's afraid of being castrated as his mother has been. And so you've got all these stories going around. And in my analysis and in my research, this is all to do with keeping feminism down and keeping liberated women quiet.

Mwitas austro afro symposium, c- print, 2022 © Helena Eribenne

On the contrary, your project "Smells Like Teen Spirit" reflects on the paradox of fame and the exploitation of young artists. How does this project engage with contemporary issues of celebrity culture and media manipulation?

Well, my photo series "Smells Like Teen Spirit" started before "The Red Shoes" and my research into shoes and feet. Although I had already been looking at Whitney Houston and Amy Winehouse and other constructed images of self-destructive female icons. I found these 1970s American teen idol magazines on the internet called Tiger Beat, and there were others, but I cannot remember what they're called now. It was really interesting to look at how they were put together to whet the appetites of adolescent girls who would, you know, tear out the posters of Leif Garrett and David Cassidy and Andy Gibb and pin them on their bedroom walls to drool all over them. These boys look so androgynous and beautiful and accessible. But somehow, I just found it so strange how they all ended up, you know, sort of dying young from drugs or how they had a completely different life to what was projected on the television screens. They were not all iconic artists but varied in talent. But they included Michael Jackson as well. So the image was completely constructed and false, and, you know, behind the scenes it was something else. It was always somehow some kind of tragic story that there wasn't really anyone that sort of got off, got free and lived a healthy happy life. Perhaps Scott Baio. So I looked at it, and I just saw this really sort of like, a capitalistic system of, you know, getting the young boy and then getting him into all this fame and how he mistakes fame for love and how he goes down this road of self-destruction that seems to have no redemption really. But it was all about selling more records. And it was just really exploitative. And it was interesting, again, going back in time and looking at these fairly innocuous pictures but really quite harmful for them trying to be stars. And it was like a consistent image of damage and destruction. It was really quite interesting and fascinating to explore the, you know, what's happening to the girls is happening also to the boys. There was no distinction there.

You've collaborated with an impressive list of musicians across experimental, krautrock, dub, and jazz genres. How have these collaborations influenced your artistic practice, particularly in performance and sound design?

Yeah, we're talking about a really long period of time that these collaborations were going on for. They were mostly while I was still living in London. Music was my primary focus, and I also did a bit of acting on the side. Over the years, since I came to Vienna, especially after studying art, I've ended up, you know, developing my practice in photography, video, and all different kinds of digital media. So, I began to focus less on being a stand-up singer to integrate different elements from my practice. I've always loved musical theatre, for example, so I love doing performances where there's poetry and song, you know, maybe one or two rather than a full on musical, as you might see in the West End of London. So, yeah, I feel that the music side has become as much of a tool as a camera, for example. It's the means of telling a story. And music is really my primary motivator. I feel I'm a minstrel above all and a storyteller. So, yeah, I would actually like to record an album and have that as an art piece as well with performance but again, not that straight ahead woman-behind-the- mic with a band, but rather a real collaborative, artistic experience, something that will, you know, be on video or digitally recorded audio, video and live and textual. I think just going down that old school road of going in the studio, recording something, releasing something, it's just so, it's so yesterday, isn't it? There are so many more possibilities.

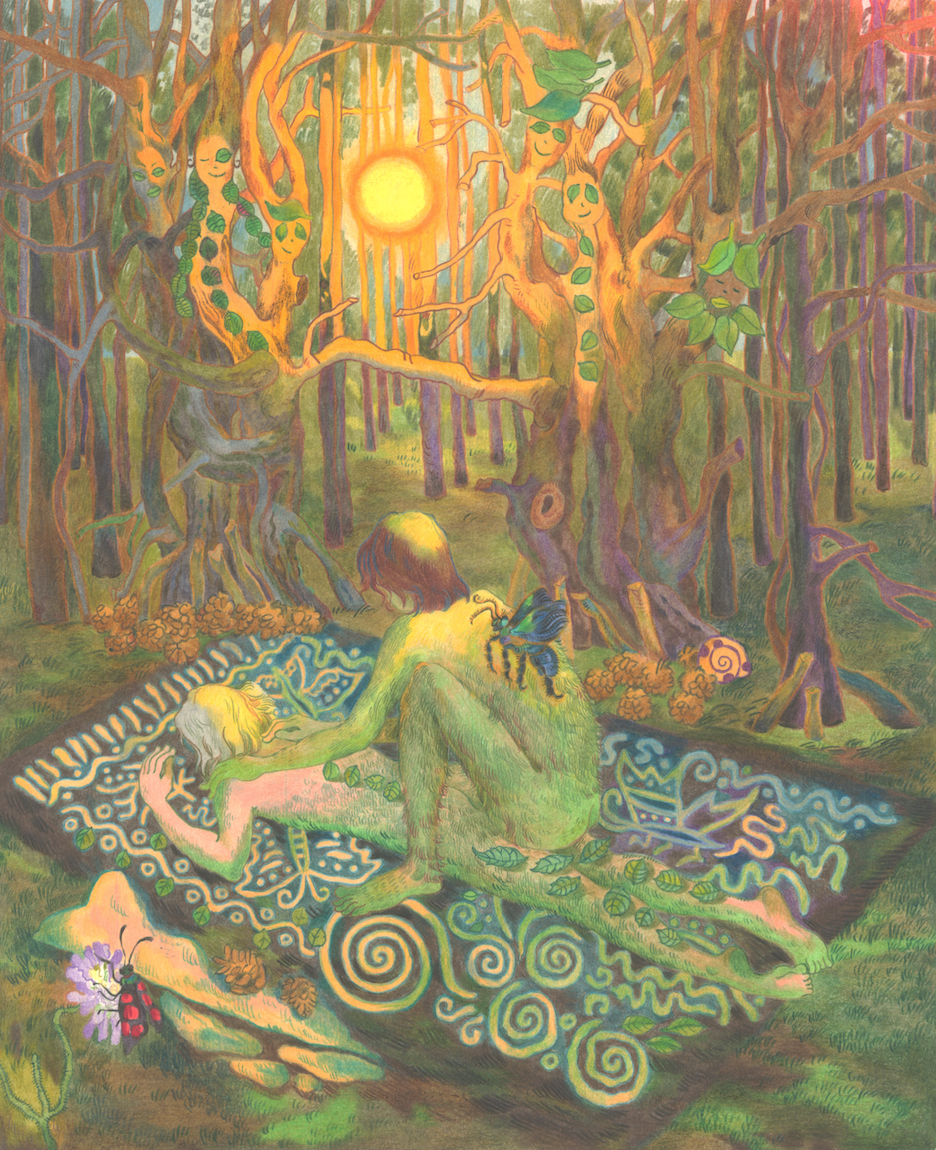

Dejan’s shamanic past and present tension, 2011 © Helena Eribenne

The reckoning, c-print, 2021 © Helena Eribenne

You recently traveled to China to study Traditional Chinese Medicine and spirituality and plan to explore West African cosmologies in 2025. How do these cross-cultural experiences inform your understanding of healing, ecology, and spirituality in your art?

Yeah, I mean, I don't want to go into too much detail about things that I have planned and are yet to be executed because, quite often, my projects are long-term and take a while to get off the ground. But yes, I went to China to study traditional Chinese medicine. And once you're in China, I was living in Shanghai, you're right, slap bang in the middle of their cosmology. It's a very modern city; however, the ancient culture of thousands of thousands of years still remains its heartbeat. You're really living in the flow of yin and yang. You can feel it even when you're cycling around town. There is this flow of energy. It's so different from Austria or Germany, where you have to stand at the red light, even if it's three o'clock in the morning and there's no traffic. You'd better stand there until it's green because, you know, a cop might be waiting around the corner to give you a ticket. In China, people just flow. If there's nothing coming, you just go. It can lead to very chaotic and haphazard results and circumstances, but I found that quite liberating. So, I want to explore West African cosmology in the same way. A lot of it, again, is in this post-colonial research of mine, from my point of view and from my family's. From my point of view, I don't want to use this word, but it's the only one that comes to mind, which is corrupted with colonial religions that were imposed, ones of Christian and Western values and cultures and the rejection of own healing cosmologies and systems and there is a revival of this going on which is what I talk about and explore with my artist collective Earth Zone Productions. It's not just the healing, it's not just a spirituality, but it's also about ecology, and it's about combining modern technology with with ancient practices the way the Chinese do it, so yeah, I'm looking for artists in residencies in West Africa to bring this ancient practice onto a, you know, a much higher level. I think it's happening already but I really want to be part of that because I really feel that I am a medicine woman, so I'm interested in plant healing and all kinds of forms of healing, and it's also a feminist act to go for plant healing as we know in the west in western civilisation uh female healers were killed because they had this knowledge of plant medicine they were called witches and they were burned and so it's not just about West African cosmologies but it's also about ecology, it's about mother nature it's about loving the earth. It's about the end of the destruction of the planet and the end of violence against women. I'm really interested in healing plants that grow wild and how they can really be used more broadly medicinally, especially in West Africa. How can we bring that onto a level that is its own kind of category, just like TCM?

Your time machine projects involve both AI technology and historical tools. Can you elaborate on how you combine modern innovations with older technologies? What is your stance on issues like AI and AI-generated art?

Well, again, before I embark on the first workshops and launch the time machine, it might be wiser for me not to divulge into how it's going to happen and what tools I'll use and what it will all look like until I've actually done it.

But my stance on AI and AI-generated art, well, I mean, depends on what you're doing. I really do love AI, and I find this whole Web3 generation of creativity so liberating. I mean, my voice is being recorded now and then being transcribed at the touch of a button for this interview, for example. And AI can just really help your workflow on a basic level. It's much faster. You can work much more intelligently. I don't think it makes you lazy but I do think it makes things easier. AI-generated art; it depends on how you use it. If you've got no artistic skills and, you know, you ask AI to come up with something, it will. As far as I'm concerned, I like the idea of using AI and technology to build things, create things, and design things. Useful things. And I think that AI is a really good way to build a time machine and travel back in time.

Hopefully you will see the final model and hopefully I'll be able to share it with you one day once we've made it. But there will be various different kinds of models built all depending on the scale of the museum, of the exhibition space, and of course on the budget.

Sandroeezanzinger, 2016 © Helena Eribenne | Photo: Sandro E. E. Zanzinger

Lastly, looking forward, what new directions or ideas are you excited to explore in your upcoming projects?

Yeah, I've got quite a few projects lined up and, from photo exhibitions, photo shoots, video shoots, research weekends.It's more of the same, but expanding, including more of my interest in Chinese cosmology, including martial arts such as Kung Fu. And, yeah, just really wanting to go more global with my art, just to reach a wider audience. It's really about being more global at the moment for me. A lot of people, I think see China as their enemy, but I don't, and I definitely want to go back. I want to work with the Shanghai Theatre Academy again, and I want to learn more about Chinese cosmology at the University of Traditional Chinese Medicine in Shanghai. And spend more time in West Africa, like longer periods of time, doing research into plants for healing. And there's the spiritual aspect, the spirituality and cosmology. It would be awesome to attend some of those festivals dedicated to the deities that are so frowned upon by the Christianised Africans. There is a fear of our own deities and ancestors – they are seen as something evil. So, there was a lot of manipulation within this colonialism and post-colonialism, as we know. I think the movement will be an uphill struggle, but I'm just looking forward to launching quite a lot of projects that I've got there. As I said before, what I am embarking on with the time machine, for example, is a long-term project, but yeah, all my projects will unfold over the coming years. I'm really looking forward to, you know, finding more collaboration partners, museums, galleries, and residencies and connecting with those who really understand what I'm doing and can help move this forward. It's helping to move the world forward in a way because this is a very special time on this planet where we are sort of like trying to reconnect with Mother Earth, rip up the concrete, plant more trees, respect nature, the earth, loving it more. I really hope that there is a relinquishing of the stranglehold of capitalism that it has over people's lives - it is pretty deadly. And, you know, there could be a stockpile of money for some if they want it, but it shouldn't cost the earth.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a promotional platform for artists to articulate their vision and engage them with our diverse readership through a published art dialogue. The artists are interviewed by Mohamed Benhadj, the founder & curator of Al-Tiba9, to highlight their artistic careers and introduce them to the international contemporary art scene across our vast network of museums, galleries, art professionals, art dealers, collectors, and art lovers across the globe.